Wyrd Times by Nigel Pennick

Nigel Pennick has written countless books, but only this one full memoir. The edition is the second in a series by Arcana Europa - ‘Wild Lives’. The first was Far Out In America by Wolf-Dieter Storl, which I review here.

https://chaotopia.com/2022/02/21/far-out-in-america-by-wolf-dieter-storl/

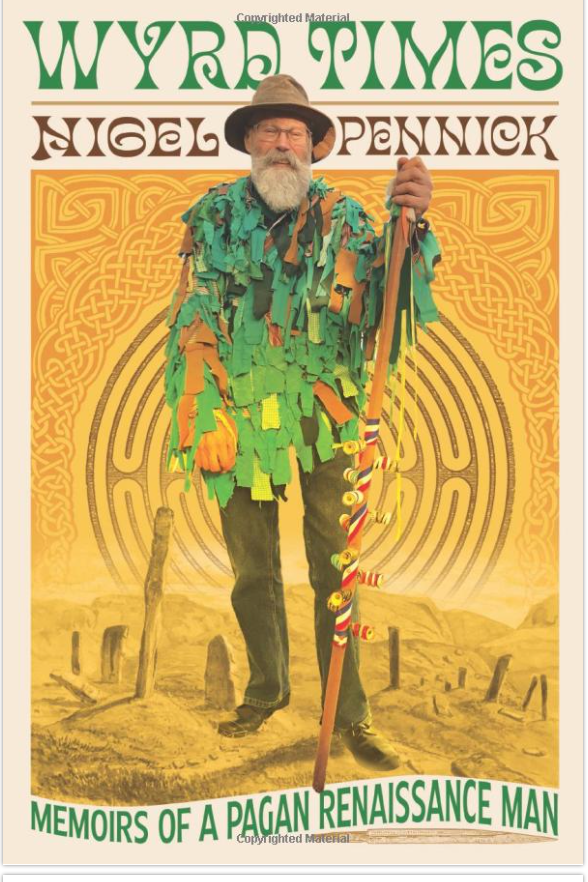

The front cover of Wyrd Times is a montage which sums up a lot of the interior - Mr Pennick stands as a giant in a landscape of standing stones, a labyrinth and Hiberno-Saxon knotwork.

This is a life-and-times book, evoking that other country, the past. I remember much of what Mr P writes about as post-war London, being only a few years younger than him. This fascinating part of the book also introduces his eye for architecture and design, especially lettering.

When we get into the 1970s much of the text is a history of his ‘underground’ publishing days, putting out many magazines of local (Cambridge) anarchist agitprop as well as an emerging theme of earth mysteries and local tradition. He writes about being an outsider even on the ‘alternative’ scene, and the hostility of the would-be leaders of the cultural avant garde, such as Arts Labs. This section has so much detail about underground publications of the time that it will probably only appeal to collectors and historians - clearly, Mr P keeps extensive records as well as having a great memory!

He writes a very interesting account of his life as a Toadman, a practitioner of a rural tradition that he talks about as being wider in scope than magic, that can’t be tied down to any single definition: ‘The nameless art is not categorizable in modern taxonomic terms’. He wrote a book about Toadmanry which is now sadly unavailable.

Nigel P is one of those people who have always been involved in organizing for pagan communities, and enacting rituals in public in England and in mainland Europe. He tells a number of great tales about the life of a pagan lecturer on the road, including miserable paranoid pagans in Preston, arguing a fanatic into the ground and trouble with Christian thugs. I share a number of his views, including a dislike for public pagan LARPing, the sort of person who fixes ‘on some imagined period and tries to reproduce it’. Rather, ’authenticity is what we should all strive for’.

He appeared on mass media a number of times, the most unpleasant being in 1984 when the BBC invited him onto a religious affairs radio show to expound paganism. The gig was a hostile setup, and the only other guest tore into him. Asked later why he didn’t walk out, he writes ‘that is not what someone of the Northern Tradition does’.

He writes about ‘keeping up the day’ - the celebration of old calendar dates before they get forgotten completely. Many of them have been eliminated by what he refers to as ‘mindless officialdom’, banning old celebrations for no good reason. He writes of has celebrating folkways at festivals in Germany and Austria as well as Morris and mumming in

England. This necessitated his travelling a good deal, and he tells a few tales of his journeys. His description of borrowing Geiger counters in Bochum to measure the fallout from the 1985 Cernobyl disaster reminded me of the night my magical group worked up in the woods in West Yorkshire at that time. The next day we learned that the rain we’d been walking through had 800 times the usual level of radiation in it.

Nigel’s chronic ill health eventually caught up with him. His attitude was that ‘the show must go on’, but after 9/11 he decided he wouldn’t be flying any more.

The later sections of the book take up themes from NP’s life, such as fonts and lettering, which convey not just verbal information but also inform through their beauty. He writes of ornate lettering from Victorian and Nouveau designs, the Arts & Crafts styles and right through to San Francisco’s Rick Griffin and the psychedelic album covers I loved in my tripped-out teens. There was an unexpected cultural bonus too in his account of his father’s interest in numerology, especially the number 23. Having been influenced in my life by William Burroughs, Discordianism and Chaos Magic, 23 is part of my esoteric DNA. I thought its association with disaster and death started with Burroughs’s reminiscences about Captain Clark, but it appears that Rupert Pennick was having 23 synchronicities at least as early as 1944. One upshot of this was his winning of enough money on the Football Pools to buy a house.

There is more in this book that I haven’t touched on. He ends one of the final chapters with reflections on death, and concludes: ‘Ultimately, we have only one option: to dree our wyrd, accepting with good grace whatever the decree of the fates brings us’.

He ends the book with some original and worthy reflections on magic. At this point I recall the title of the Prologue, from the Old Sussex declaration ‘We wunt be druv (driven)!’ Anyone who will be ‘druv’ is not going to make it as a magician.

The subtitle of the book - Memoirs of a Pagan Renaissance man - is very apt. NP is a master geomant; that is one of the things that holds together his immense range of Renaissance man learning - design, architecture, the earth, magic, folk traditions and science, especially biological. Anyone who has heard him talk will probably agree that his talks are structured as rambles, but not in the sense of incoherence. His delivery is more in the style of a fascinating walk with a man who is learned in many subjects. This is the overall style of the book, a walk through a highly articulate man’s life and times. I’d recommend it for those reasons, and because it reveals something of the inner world of a man who has lived magic for decades. However, the downside is that some parts of the book read like just lists of events and productions, a CV, without any interior dimension.

Comments

Post a Comment